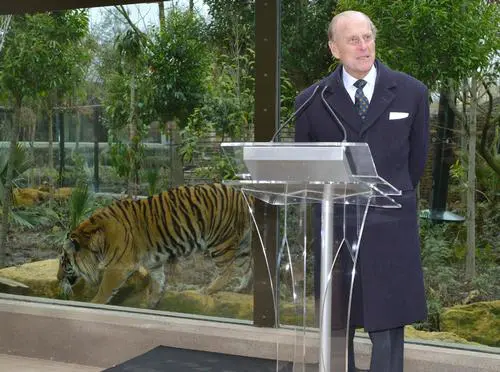

In March 2013, the Duke of Edinburgh unveiled London zoo’s newest pride project — Tiger Territory, an “Indonesian-inspired” enclosure for two Sumatran tigers, Jae Jae and Melati. The price: £3.6 million, or about US$4.5 million. The justification: conservation. The reality: captivity.

The exhibit, covering 27,000 square feet, is five times larger than their previous cage — still 99.999% smaller than their natural range. It boasts trees, rocks, and a swimming pool. It’s a zoo’s fantasy of wilderness — a curated illusion sold as education. London zoo calls it “a new home.” But the tigers already had one: the forests of Sumatra, where fewer than 400 of their kind still fight for survival. In those forests, the same money could have funded over 100 anti-poaching rangers for a decade, or restored thousands of hectares destroyed by palm oil and logging.

The illusion of conservation

As celebrated by Sports Management, the project was hailed as “the zoo’s biggest investment since Gorilla Kingdom.” That statement says everything about priorities. While wild tiger habitats collapse, institutions that profit from captivity continue to expand, calling concrete compassion. Zoos across the world repeat the same narrative: “awareness equals protection.” But awareness without action is indulgence — the kind that fits neatly into a marketing brochure.

Visitors are told these tigers are ambassadors for their species. But ambassadors are meant to travel freely — not pace glass walls. The breeding ambitions attached to the project are dressed up as “insurance populations.” Yet captive breeding rarely contributes to wild recovery. Most cubs born behind bars will never leave them. They are born into extinction’s waiting room, raised for visibility, not viability.

Money spent to feel better

The £3.6 million (US$4.5 million) could have transformed tiger conservation where it matters most. It could have reinforced patrol units in Indonesia’s national parks, purchased drone surveillance for poaching hotspots, and funded community livelihoods that reduce hunting pressure. Instead, it built skylights, fences, and viewing decks.

This is the global pattern: build cages in rich countries and call it empathy, while the wild starves for funds. Less than 3% of zoo revenue worldwide goes to in-situ conservation. The rest fuels operations, expansion, and entertainment. London zoo’s Tiger Territory is not an act of saving — it’s an act of substitution, where the illusion of care replaces the responsibility to protect.

When captivity becomes comfort

The public loves the story. Two “genetically matched” tigers brought together for a breeding dream. But breeding in confinement is not conservation. It is reproduction for profit. Each cub born in captivity becomes another justification for the institution’s existence. Each camera flash is proof of public satisfaction — not species survival.

These tigers live under perpetual observation. Their every movement is filmed, studied, and marketed. Yet the same organizations that claim to safeguard their species have failed to secure even 10% of Sumatra’s original tiger habitat. The contradiction is complete: celebrate life behind bars while ignoring the deaths beyond them.

The real price of spectacle

This is not just about one zoo. It’s about a global appetite for guilt-free consumption of nature. People prefer their tigers close enough to photograph — not far enough to protect. The illusion is comforting: that by visiting a zoo, one becomes part of a solution. But the £3.6 million investment reveals the opposite. It’s not the tiger being saved; it’s the human conscience being soothed.

Imagine if every visitor who buys a ticket contributed instead to the rangers who patrol Gunung Leuser, Bukit Barisan, or Kerinci Seblat — real strongholds of the Sumatran tiger. Imagine if London zoo had turned Tiger Territory into a virtual experience that funds the wild instead of imprisoning it. That would have been conservation.

The cost of captivity

London zoo will showcase Tiger Territory for decades, its plaque gleaming, its pools cleaned, its trees maintained. Meanwhile, the wild from which these tigers came continues to vanish. The London zoo will call its exhibit a success when cubs are born, destined for a life behind bars. But success would have meant no need for cages at all.

Captivity is not rescue; it’s resignation. The true tragedy is not that London zoo spent £3.6 million (US$4.5 million) — it’s that it could. Because the world still believes that seeing a tiger up close is more important than ensuring one survives unseen in the wild.

Until that illusion breaks, the wild will keep paying the price of human comfort. And every cage, no matter how golden ,like in the London zoo, will remain what it always was — a monument to what we failed to protect.

Source: Sports Management, UK

Photo: Sports Management, UK