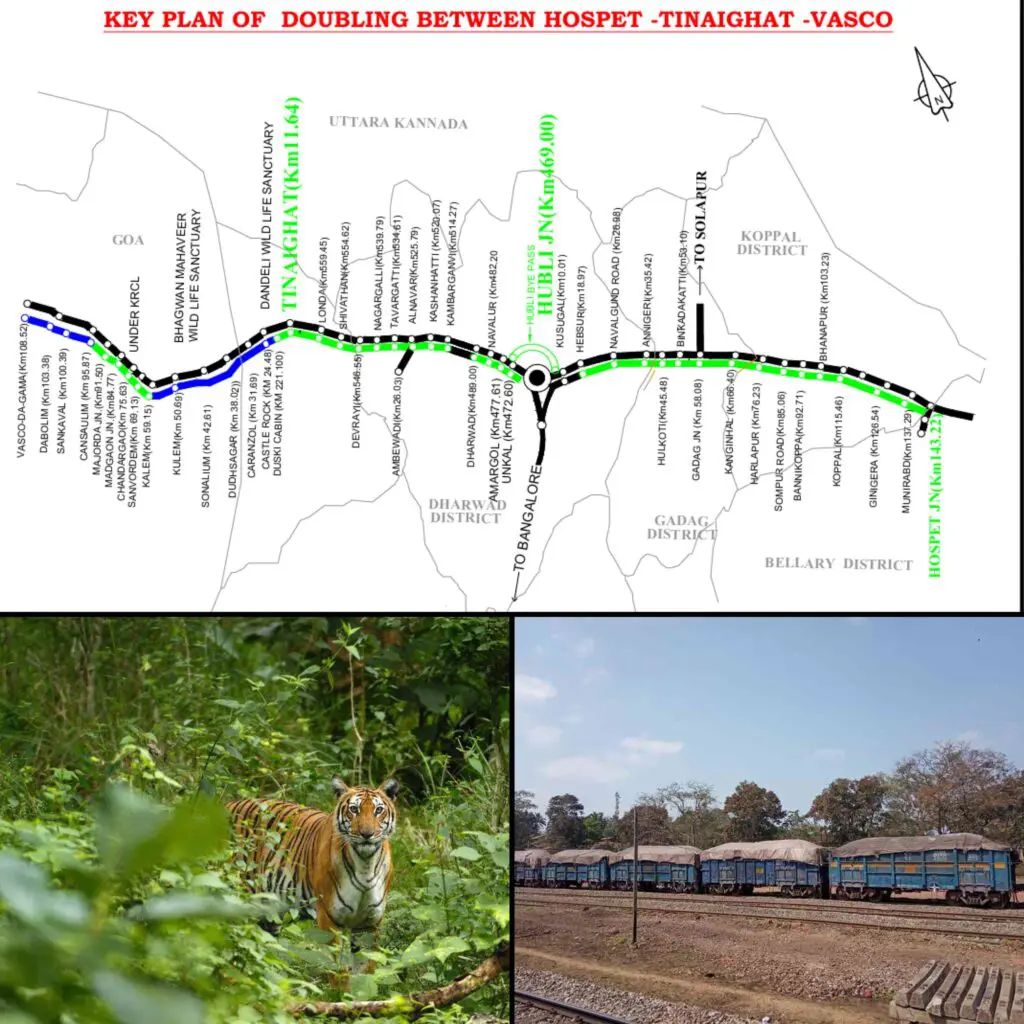

A single line of steel is about to redraw the map of India’s wild south, as reported by Scroll.in. The government’s plan to double the railway for coal transport between Hospet in Karnataka and Vasco da Gama in Goa will cut straight through the heart of tiger country — an ecological artery that has kept the Western Ghats alive for millennia. The project’s 345-kilometre route will become the country’s most destructive trade line yet, built to feed coal transport demands at the cost of forest, silence, and life.

The Wildlife Institute of India, in its field assessment commissioned by the Rail Vikas Nigam Ltd, confirmed tigers, leopards, and dholes along the route. Its camera traps caught adult tigers with cubs at five locations. The same report recorded 341 wildlife-rail collisions in eighteen months — 76% amphibians, 16% reptiles, and nearly 8% mammals. Still, officials describe the coal transport plan as a “manageable impact.” The contradiction is striking: a study that proves fragility has been used to justify destruction.

The tiger corridor becomes a coal corridor

The Western Ghats are not just another mountain range — they are a living corridor that connects twelve tiger reserves, twenty national parks, and sixty-eight sanctuaries across six states. The proposed double-tracking turns this corridor into a conduit for coal transport, forcing trains through Dandeli Wildlife Sanctuary, the Kali Tiger Reserve, and Goa’s Bhagwan Mahaveer Sanctuary and Mollem National Park. In bureaucratic terms, this is “infrastructure optimization.” In ecological terms, it is erasure.

The National Board of Wildlife’s clearance was already quashed by the Supreme Court in 2022. Even the National Tiger Conservation Authority warned that doubling tracks through Kali would be detrimental. Yet Rail Vikas Nigam Ltd returned with the same project and new paperwork, claiming a “benefit-to-loss ratio” of 436 to 1. What that really means is that for every rupee lost in forest, 436 will be made in coal transport. That number doesn’t measure progress — it measures consent to extinction.

The illusion of mitigation

Authorities claim they will install 323 “mitigation structures” — culverts, underpasses, and bridges — to make the coal transport route safer for animals. But conservationists have heard this before. These projects always promise balance and deliver absence. Train noise, vibration, and speed cannot be mitigated by cement. Each overpass becomes a token, each fence another barrier. The government calls it coexistence; ecologists call it surrender.

The Western Ghats are already losing ground to plantations and hydropower. As detailed in mining and tigers, every industrial expansion — whether for ore, oil, or coal transport — chips away at the land that gives India its rainfall, rivers, and resilience. Forests once alive with tiger calls now echo with the clatter of commerce.

The cost of coal transport

The most dangerous claim in this debate is that “not a single tiger has died on this line since 1890.” The statement, repeated by project engineers, hides behind absence of evidence. There were no cameras then, no sensors, no monitoring. Today, there are — and the data reveal what denial once buried. Tigers still use these routes. Elephants and gaur cross them. Amphibians and reptiles are killed by the hundreds. A railway designed for coal transport cannot double as a wildlife corridor.

Even the Supreme Court’s Central Empowered Committee proposed an alternative: reroute freight via Andhra Pradesh’s Krishnapatnam Port. The suggestion was logical, cost-effective, and ecologically sound. It was ignored. The message was clear — the coal transport agenda must not be slowed by science.

A battle of priorities

This is no longer a debate about tracks. It is a debate about what kind of nation India wants to be — one that moves coal or one that moves conscience. Goa’s Amche Mollem campaign has fought relentlessly to protect these forests, supported by biologists and artists who see what policymakers refuse to: the Western Ghats are not a resource, but a refuge.

Tigers, leopards, elephants, and countless endemic species survive here not because of mitigation, but because there were once limits. Those limits are now being rewritten. As coal transport expands, the tiger corridor contracts. If this project proceeds, it will set a precedent for every forest in India — that industrial convenience outweighs ecological continuity.

The silence ahead

India celebrates its tiger numbers every decade, but those numbers mean nothing if corridors vanish. Forest without movement is forest without life. Once a track divides the Ghats, the damage is irreversible. Coal transport will become the permanent background noise of extinction — an echo that never fades.

Economic growth does not need to come at the price of annihilation. But for that to change, the government must see the Western Ghats not as a coal route but as a living, breathing system that sustains the south. Until then, the country’s coal transport dreams will keep burning the very wilderness that keeps it alive.

Source: Scroll.in, India

Photo: Scroll.in, India