Introduction — The New Gold Rush

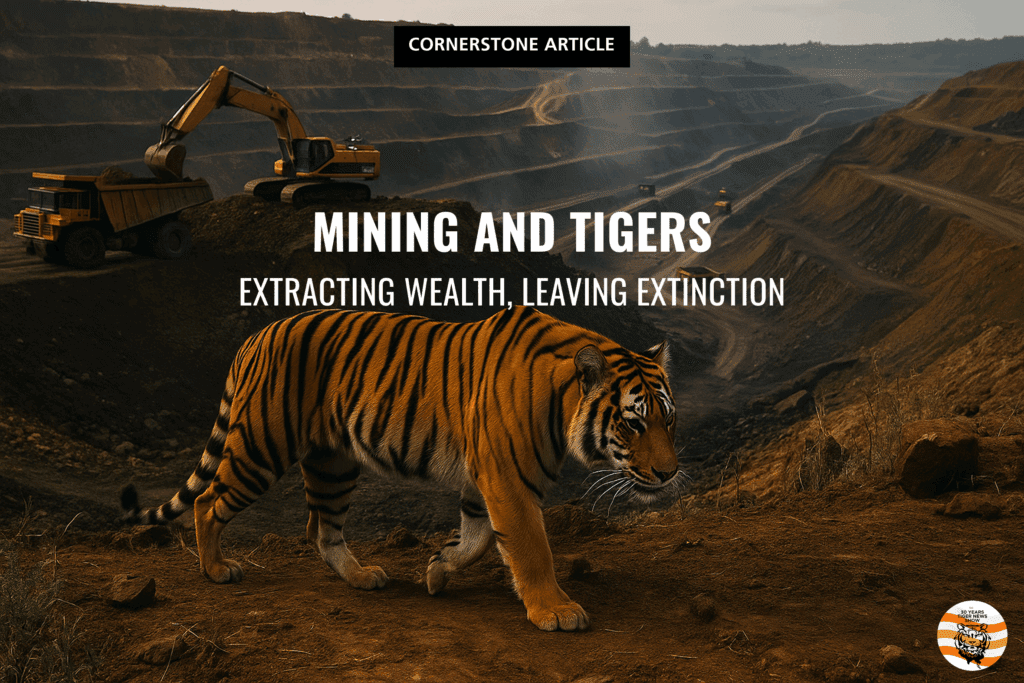

Across the tiger range countries, the newest gold rush isn’t gold at all. It’s coal, nickel, iron ore, bauxite, rare earths, and stone—the raw inputs of concrete skylines, smartphones, batteries, and export-led growth. Mining.

Governments pitch mining as salvation: jobs for the poor, energy for the grid, foreign currency for public services. But in the forests where tigers still hold a line against oblivion, each prospecting grid, access road, and pit mouth becomes a subtraction problem that only ends one way. Mines don’t just remove rock; they remove silence, connectivity, and the living scaffolding that makes a forest work. Camps bring meat markets; haul roads become poachers’ highways; tailings leach into streams that feed deer and boar. The ledger that politicians show on television never includes the line item where a corridor breaks, a breeding female disappears, and a population sinks below the threshold where chance can’t help.

That invisible accounting—biodiversity, water, health, social cohesion—is treated as “externalities,” a word for costs someone else is asked to carry. The reality is blunter: mining concentrates profit and pushes risk outward, onto communities and species with the least political protection. When the mining marketing deck says “balanced development,” the field report reads “fragmentation.” For tigers, whose survival depends on contiguous habitat and quiet passage between it, extraction is not a headline or debate. It’s a map of disappearance.

Mining inside tiger landscapes

Look at a tiger-distribution map overlaid with mining concessions and you see the collision: coal belts threaded through central India’s reserves; nickel tenements nibbling Sumatra’s outer edges; quarry leases in forest fringes where camera traps still find stripes at night. In Russia’s Far East, gold dredging and coal edges creep toward Amur tiger territory; across mainland Southeast Asia, small hard-rock sites punch scattered holes into what should be continuous cover.

The first physical footprint of mining is almost always a road—a narrow incision that looks harmless on paper. But roads change everything: more people, more guns, more snares, and more noise where silence was a resource for reproduction. What follows are clearance yards, diesel depots, and power lines that carve linear gaps across the understory. A corridor that once funneled shy dispersers between breeding blocks becomes a hazard course.

The science is old but ignored: even “limited” disturbance can flip prey behavior, pushing them into cropland and triggering conflict that ends with compensation bullets. On the mining plan, these impacts are “mitigated” by paper buffers and set-asides. On the ground, buffers shrink to ribbons of second growth that never carry a tigress and cubs safely through.

The cheapest claim in environmental paperwork is that habitat is “degraded” already. The cheapest lie is that removing more of it will make no measurable difference.

Permits, politics, and the rubber stamp

Extraction is a political product long before it is a geological one. Mining leases cross desks lined with party banners; consultants write impact studies for the very clients they must critique; “public hearings” are held in towns far from affected hamlets. When objections break through, ministries split jurisdiction until responsibility dissolves: industry issues the lease, environment stamps the clearance, forests negotiate “compensatory” plantings, and wildlife is invited to comment on a timeline designed to exhaust it.

The euphemisms—“strategic minerals,” “national interest,” “expedited approvals”—sound like leadership but function like blindfolds. If you follow the trail beyond acronyms, you reach the engine room we exposed in our cornerstone on Political Failure & Corruption: campaign finance tied to concessions, regulators seeking post-retirement seats on corporate boards, and enforcement chiefs rotated away when they ask a hard question.

In that system, the toughest law is only as strong as the weakest phone call. Appeals buy time, time dulls outrage, and the bulldozers arrive on schedule. By the time a court demands a cumulative impact study on the mining, the “cumulative” part has already happened—on the forest floor, in the streams, and in the shrinking buffer that once made a tiger’s night walk uneventful.

Communities displaced, knowledge erased

In every range state, the first human cost of mining falls on people with the most to lose and the least to gain—Indigenous and forest-dependent communities who know the land by memory, not map layers.

Relocation frameworks promise equity but deliver thin shingles of cash, insecure plots, and a vanishing trail of jobs. The permanent loss isn’t just a house; it’s knowledge: where the springs hold through dry months, where boar cut across, where a tigress prefers to den in late rains. That knowledge anchors coexistence. Remove it for mining and the forest fills with strangers—contract workers with no stake in the rhythms of a place.

Camps push hunting pressure higher; charcoal fires and casual snaring become routine. People who understood when to clear and when to leave a slope alone are replaced by schedules that obey neither monsoon nor mast year.

A second erasure follows: dignity. When grievance channels fail and promises curdle, recruitment for illegal work gets easier—timber, bushmeat, or couriering wildlife parts along the new road. Community patrols that once tipped off rangers stop calling.

You can read displacement as a budget line or as a slow-moving disaster that destabilizes both conservation and democracy. Either way, the outcome echoes: fewer allies for the tiger in the place it needs them most.

Pollution and poisoned prey

Not all mining harm looks like a clear-cut. Heavy metals ride the dry season wind; fine mining coal dust coats leaves that deer and gaur depend on; acid mine drainage eases through culverts into streams where fish once laid eggs in clean gravel.

The chemistry is simple and unforgiving: lower aquatic productivity, fewer fish, less otter and waterbird life, less prey gathering at reliable water, and more hungry predators testing the edges of villages for goats. In karst belts, limestone extraction drops the water table and turns perennial seeps intermittent; in peatland margins, spoil heaps smolder and seed fires that unwrap the canopy for miles. None of this fits neatly into an environmental report’s “residual impacts” box, but it shows up in clinic ledgers—skin lesions, coughs that don’t end, miscarriages clustered near tailings.

When officials say there is “no evidence” of biodiversity loss due to mining, they often mean no funded monitoring exists to demonstrate what residents already know. A tiger’s life is built on a chain of inputs so ordinary they’re invisible: water that doesn’t burn the nose, forage that photosynthesizes through the dust, and salt licks not laced with arsenic.

Break enough links and a population remains in place only on brochures and billboards.

Corridors cut by linear infrastructure

Mines run on arteries: feeder roads, haul highways, rail spurs, pipelines, and power lines. For tigers, every straight line is a problem. It isn’t only traffic mortality or the direct loss of cover; it’s behavior. Prey avoid noise and glare; predators follow prey; conflict follows predators.

In central India, models show that adding a single four-lane road across a narrow forest neck cuts functional connectivity by more than a third. In Sumatra and peninsular Malaysia, parallel rail and road corridors around pits squeeze animals toward settlements where they become news stories and statistics. The mining industry response is often “wildlife crossings” and “smart fencing,” good ideas when built, rare in practice, and often stranded by poor placement or zero maintenance.

The cheapest fix —no-go zones for mining in known corridors— remains the least used because it demands the one commodity procurement can’t supply: political will. If a landscape is to move tigers between strongholds, the line that matters is not an access track but a veto—here, you do not build. Everywhere else, build better and think longer than the election cycle.

Corruption and the illusion of regulation

Most, but surely not all, tiger range countries now have environmental laws thick enough to door-stop a ministry. On the ground, enforcement is thin enough to slip under one.

Audits are announced weeks in advance; self-reporting passes for compliance; cumulative impacts are sliced into “phases” until each appears harmless. When a spill hits headlines, committees convene, write measured prose, and dissolve. Fines become a business cost; non-compliance becomes a tactic.

The root isn’t policy; it’s power. Where mining concessionaires underwrite campaigns, the referee eats at the club of the team he’s meant to police. That’s why anti-corruption and financial-crime tools —not just environmental statutes— belong at the center of field protection. If a mining company can sign away a buffer forest with a donation, the response can’t be another awareness workshop. It has to be seizure, disqualification, prison.

Our politics rarely delivers that clarity because mining is a patronage engine: contracts, trucks, security, catering—each a small loyalty bought. Regulation looks real; capture is realer.

Until wildlife agencies marry their cases to money trails, the “rule of law” will remain an aesthetic, not a system.

Corporate greenwashing in high-definition

Every bad actor now speaks fluent ESG. Annual reports feature tiger silhouettes and children planting saplings in neat rows.

“Net-positive impact” is the favorite line; “net-present damage” is the missing one.

Certification labels, when honest, can curb the worst. Too often they are built on checklists a skilled compliance team can pass with tidy binders and friendly auditors. The contradictions aren’t subtle. A mining firm can finance a camera-trap grid while blasting the ridge that made that grid worth running. It can sponsor “human–wildlife coexistence” workshops while bulldozers tip residents into a cash-for-keys scheme that dissolves in six months.

The point of greenwashing isn’t to fool experts; it’s to flood the zone with claims until citizens tire of arguing. There’s only one way to cut through: verification at scale, in public. Tie every claim to a satellite time series, every offset to a living, diverse hectare, every “community consultation” to the signatures of the people who will live with the decision.

In a world where mining PR budgets can buy anything except old-growth, the test for truth has to be visible from space and legible to neighbors.

Global demand, local damage

The supply chains that begin under excavator teeth end under glass in wealthy markets. Nickel rides into batteries; bauxite into aircraft; coal into steel; rare earths into motors and screens. Consumers never see the line where a tigress used to take her cubs across at dusk. That invisibility is by design: long chains, many hands, exporters between extractors and brands.

The moral geometry is simple: benefits flow uphill; harm runs downhill. When demand spikes—for construction booms, energy crunches, or “green” transitions—ports, mills, and smelters squeeze their vendors. Vendors squeeze operators. Operators squeeze forests and people. The fix isn’t guilt at the checkout; it’s procurement layers that make dirty inputs unbankable. Customs and trade rules can require proof of origin that is more than a stamp. Banks can classify habitat destruction as a financing risk equal to fraud.

When mining boardrooms fear losing market access for tainted ore, you won’t need a speech to save a corridor. You’ll need a rule. Until then, every new flagship product arrives with an untallied invoice paid in rivers and stripes.

Financial crime, shell companies, and secrecy

Follow the trucks and you’ll catch a foreman. Follow the money and you’ll meet the reason mining keeps beating petitions.

Over- and under-invoicing shuttle profits into places auditors can’t reach; shell firms hold leases; nominees sign documents; export codes blur what’s in a container. Royalties travel into “special purpose” accounts that escape open-budget scrutiny. Campaign funds reappear as hospitality contracts. None of this belongs to the environment ministry, and that’s the problem.

To defend a tiger landscape, you have to move beyond wildlife laws into anti-money-laundering, anti-corruption, tax, and securities regimes. Freeze assets when a river turns orange. Bar beneficial owners who hide their identity from holding leases. Make cumulative harm a trigger for mandatory prosecution—not a bargaining chip for a bigger “compensatory” payment.

When the calculus changes from “How much is the fine?” to “Will we lose everything and go to prison?,” behavior changes before a single patrol gets a new truck.

Until then, secrecy will remain the most profitable mineral in the ground.

Resistance, reform, and what actually works

Even in hard landscapes, pushback moves policy. Courtrooms have halted pits at the lip of reserves; village councils have vetoed projects under community-rights laws; journalists have forced ministries to publish concession maps that were “not available” for years. Some tools scale well: no-go maps for critical tiger habitat and corridors; independent ecological impact panels chosen by lottery, not by tender; real-time satellite dashboards that let citizens check what companies assert; and community-owned restoration funds that pay locals to heal what outsiders ruined.

The hardest reform is the simplest to describe: keep mining out of the living core and the connective tissue that makes the core meaningful. In buffer belts and multiple-use zones, demand standards that would make an accountant wince: loud bonds, heavy liability, and automatic suspension when monitoring goes dark. Tie every enforcement unit to a financial-intelligence officer. Reward rangers for evidence that holds in court, not just for kilometers walked. Most of all, make the politics visible. Publish who paid for whose campaign. Publish who sits on which board. Publish which cases died and why.

Sunlight won’t plant a tree, but it will stop a bulldozer more often than a press release.

Outro: The Real Cost of Extraction

Tigers do not ask for favors from us. They ask for what the forest owes them: cover, quiet, prey, and a way through.

The reason they are losing that simple bargain is not geology but governance. Rocks didn’t choose to move; people did, and they used mining to translate land into money with a speed that biology can’t match.

If a country insists on counting progress by the weight of ore, it should at least count the weight of everything that ore displaces: the springs that run brown, the nights that get loud, the tracks that go silent. There is nothing inevitable about extraction in a corridor, nothing natural about a pit in a reserve’s shadow. Those are political choices, not scientific necessities.

The blueprint for survival isn’t mystical. Declare what must never be dug, enforce it without fear, and make every other decision visible enough that lies can’t find shade. We’ve known for decades that when the legal, financial, and moral prices of killing a forest are lower than the profit of doing so, forests die and tigers with them. The inverse is also true.

Raise the price of destruction and lower the friction for honesty, and stripes will return to paths where the only industry is wind and leaf. That’s not ideology; it’s arithmetic—with life on the right side of the equals sign.

When the machines stop and the dust settles, the silence that follows is not peace—it’s absence. Forests do not grow back on receipts, and tigers do not return to noise. Every generation must choose what it digs for: quick wealth or lasting worth. The choice defines more than policy; it defines civilization itself. If the tiger disappears from the map, it won’t be because we ran out of resources—it will be because we ran out of honesty.