Introduction: Science as an Ally for Tigers

Science was meant to rescue the tiger, not to rationalise its disappearance. Across tiger range countries, the very discipline created to expose ecological truth has become an instrument for concealing it. Reports grow thicker while forests grow thinner.

Budgets praise “data-driven conservation” even as patrol posts run out of fuel and prey vanish. Real science should reveal failure so policy can act; instead, it often hides failure so bureaucracy can survive. The tiger, reduced to a number, now lives inside spreadsheets more than forests.

When research replaces responsibility, knowledge becomes camouflage for political convenience. The following sections outline eight ways in which science—once the tiger’s ally—now obstructs its survival, and how that alliance can be rebuilt through honesty, transparency, and duty.

Counting as competition

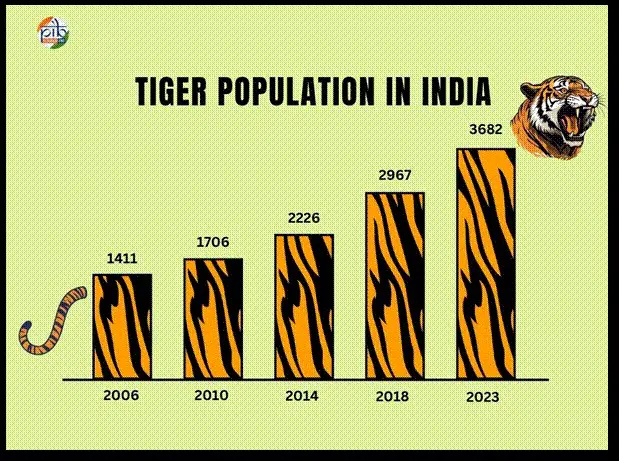

Every four years, new tiger numbers appear like corporate earnings reports. The 2022–23 All-India Tiger Estimation announced 3 167 tigers—exactly 200 more than the previous count. It was presented as proof of progress, not a question demanding scrutiny. Independent biologists quickly noted the political convenience of such arithmetic.

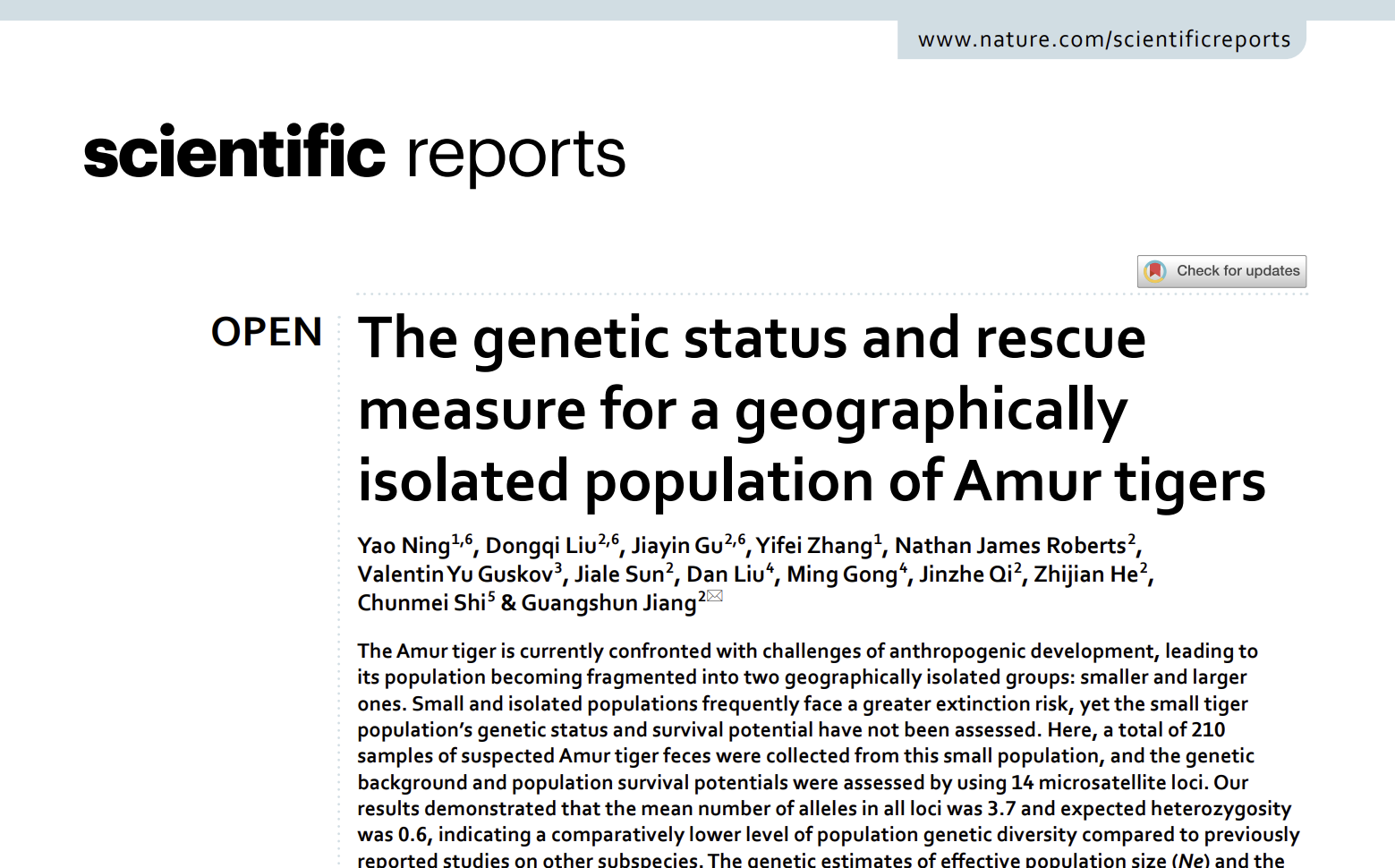

A study in ResearchGate (“Monitoring Tigers with Confidence,” Cambridge University Press, 2019) warned that extrapolating limited camera-trap data across vast unsampled areas inflates certainty and invites complacency. Similar patterns occur elsewhere. Nepal scales densities from small sites to entire eco-zones; Russia compares winter snow-track surveys taken under entirely different conditions. Each country chases an upward curve because optimism earns political dividends. Numbers become propaganda; statistics replace strategy.

These inflated successes dull urgency. When national totals rise, governments redirect funds from ground protection to publicity. Donors interpret the curves as victory and shift money from rangers to gadgets. Scientists working under state contracts are pushed to echo good news. Questioning results risks losing access. Real conservation science would open its datasets, publish error margins, and treat decline as data, not shame. Until counts are independently audited and raw files shared, the tiger census will remain a marketing exercise—useful for conferences, meaningless for survival.

The harm runs deeper than bad math. False confidence shapes land-use policy. Forests near “high-density zones” attract tourism concessions; marginal habitats are quietly reclassified for roads or mining because they seem “tiger-free.” Thus, the very science designed to protect range becomes the paperwork that erases it. A genuine count would show absence where intervention is needed most—and that is precisely why it is avoided.

Selective sampling and invisible failures

Field science depends on permission, and permission depends on politics. Researchers are steered toward flagship reserves where success photographs well. Trouble spots—corridors choked by agriculture or mining, forests leased to logging or palm-oil firms—remain unstudied.

In 2021, the Centre for Policy Research in India documented how research permits cluster around showcase parks while degraded landscapes stay off-limits. Across Southeast Asia, TRAFFIC 2020 found identical bias: studies proliferate in secure zones and vanish where governance fails. Peer-review culture reinforces it. Journals crave strong results; crisis data full of gaps is hard to publish and harder to fund. The outcome is a scientific map that over-represents stability and under-reports collapse.

This is not accidental—it is structural self-censorship built into the conservation economy.

What disappears with the missing data is accountability. Without evidence of decline, budgets remain tied to the same comfortable geographies. Patrol units stay concentrated in parks already patrolled; ranger numbers stagnate where encroachment explodes. By avoiding failure, science protects bureaucracy. The tiger’s worst habitats vanish twice: once biologically, then statistically.

The only cure is transparency. Monitoring frameworks must include a mandatory rotation of “red-flag” landscapes chosen for risk indicators—illegal roads, prey depletion, fresh snare reports. Their findings, favourable or not, should be published within twelve months. Conservation money must follow evidence, not image.

International donors share the blame. Agencies funding “evidence-based conservation” rarely demand open data or independent verification. Progress is measured through deliverables—workshops held, drones purchased—not outcomes. This creates a feedback loop where governments feed donors the data donors wish to cite. In that loop, science ceases to be observation; it becomes performance.

Overreaction to anomalies

In February 2024 a dazed Amur tiger wandered through the Russian village of Filippovka. Footage of the big cat staggering through snow went viral. Within hours, speculation of canine-distemper swept social media; within days, consultants across Asia were drafting proposals for continent-wide vaccination programs. Three weeks later, the Amur Tiger Center confirmed the truth: the animal had been poisoned by tainted meat.

A local criminal act had become a global panic.

Budgets were temporarily diverted to disease monitoring while the real issue—illegal baiting—went unaddressed.

This reflex illustrates a larger pathology: the substitution of spectacle for scale. When an isolated incident dominates international attention, systemic threats fade. The same happens when a tiger strays into farmland or attacks livestock. Governments form committees, television crews arrive, and scientists produce risk assessments detached from geography. The root causes—fragmented corridors, dwindling prey, weak compensation policy—remain untouched. Good science distinguishes signal from noise; bad science monetises the noise.

Every misplaced research dollar is a snare left uncut, a ranger unpaid.

Different landscapes require different medicine. Disease surveillance is vital in Siberia but irrelevant to the snare belt of Southeast Asia; conflict mitigation in central India demands social anthropology more than veterinary tools. Yet bureaucracies prefer one-size solutions because they are administratively simple and globally marketable. When every anomaly triggers an international template, science becomes another export industry detached from local reality. The tiger pays for this homogeneity with its life.

There is also opportunism. Crises attract grants. Announcing a “new threat” can secure funding faster than documenting an old one. The 2024 poisoning episode proved it: misinformation generated budgets, not reforms. True scientists should resist the adrenaline of alarm and anchor their work in verification. In the age of viral data, patience is rebellion.

Technology worship and field neglect

Drones, satellite collars, AI image recognition, and eDNA kits dominate conference agendas. They symbolise progress and modernity, yet the tiger’s survival still hinges on the basics: fuel, food, salaries, and political will. In many reserves rangers walk patrols in broken boots while ministry officials pose beside prototype drones. Technology is the new theatre—equipment that looks like enforcement but costs less political courage.

Governments adore gadgets because they yield clean graphs; donors adore them because they produce deliverables. Yet gadgets cannot arrest poachers or rebuild prey populations. The 2024 WCS State of Big Cat Conservation Science Report warned that “technological optimism must not replace institutional accountability.” A drone may locate a snare, but only a ranger can remove it. Without human presence, the most sophisticated system is an expensive illusion.

Field neglect hides beneath digital dashboards. Governments measure progress by data uploaded, not patrol hours completed. International NGOs reward innovation grants rather than salary support. A culture of metrics replaces a culture of responsibility. When a tiger dies in a snare, the press release that follows cites “lessons learned” and “future monitoring protocols,” as if syntax could resurrect the animal. Science becomes public relations. Conservation is measured in terabytes, not tigers.

The obsession with data science distracts from the question that matters: who still dares to walk the forest when no one is watching?

Funding distortion and paper-chasing

Modern wildlife research runs on grant cycles, not ecological timelines. A doctoral student must deliver publications within three years; a conservation NGO must show “outputs” before the next donor review.

This temporal mismatch erodes depth. Long-term monitoring—essential for detecting population trends—rarely fits funding logic. The result is shallow science: studies that end when the money does. Researchers design projects for statistical neatness rather than field necessity. A 2023 meta-analysis in *Biological Conservation* found that over 70 % of tiger-related studies last less than two years. That brevity might satisfy peer-review productivity but tells us little about generational survival.

Grant dependence also shapes questions. Proposals that promise technology, novelty, or international collaboration are prioritised; projects exposing corruption, weak enforcement, or government failure are not. Scientists adapt by writing what donors want to hear. Peer reviewers—often from the same funding ecosystem—reinforce the cycle.

Thus the appearance of science persists even when its independence erodes. The tiger becomes collateral in a contest for citations. The few long-term datasets that do exist—like the 25-year monitoring at Kanha and Chitwan—owe their survival to local dedication, not to any global mechanism. Replicating that model would require a revolution in priorities: paying for patience rather than novelty.

Paper-chasing harms communication too. When results are locked behind paywalls, rangers and community leaders who could use them cannot. Knowledge stops where English begins. Translating research into local languages or operational manuals brings no academic credit, so it rarely happens. The outcome is tragic absurdity: villagers on the forest edge may never read the science that defines their future, while researchers win awards for “community engagement.”

Duty cannot be outsourced to the citation index.

Bureaucratic censorship of inconvenient results

Few governments openly destroy data; most simply suffocate it. Draft reports critical of development projects vanish into “review.” In 2022 India’s Ministry of Environment issued a circular requiring pre-clearance before publishing research from protected areas. Thailand and Myanmar have similar provisions. The justification is “national security”; the effect is silence. Scientists who bypass clearance risk being blacklisted.

Even international partners tread carefully. A 2023 Reuters investigation quoted Thai biologists admitting they self-censor to keep field access. The same pattern appears in Russia, where independent ecologists monitoring illegal logging near tiger habitat lost permits after criticising local officials. And let’s not forget China, where everyone is afraid to mention anything that can bring China in a bad light.

When evidence threatens political comfort, evidence disappears.

Corruption compounds censorship. Environmental impact assessments are written by consultants hired by the very companies they assess. Peer reviewers are chosen for compliance, not competence. In this system, failure is invisible until the next catastrophe. The UNODC 2024 World Wildlife Crime Report described how “data opacity enables trafficking to flourish,” noting that weak transparency in range-state ministries correlates with higher seizure volumes.

The pattern is mathematical: secrecy breeds poaching. Yet scientific institutions seldom protest; they depend on the same ministries for permits. Silence becomes collaboration.

The moral damage is immense. Young scientists learn caution instead of courage. Conservation NGOs publish only what sponsors approve. Entire ecosystems become research-free zones precisely when scrutiny is needed most. To restore integrity, tiger science must adopt the ethics of journalism: verify, publish, and defend the truth regardless of hierarchy. A ranger who reports a snare risk does more for science than a bureaucrat editing an abstract.

Until this hierarchy reverses, knowledge will remain captive even as tigers disappear.

Exported models that erase local realities

Global conservation moves in waves of fashion. One decade it is “landscape connectivity,” the next “nature-based solutions.” Each slogan arrives with templates designed far from the forests they claim to protect. When these imported models meet local realities, nuance dies first. India borrows metrics from African savannah studies that assume open grasslands; Indonesia applies corridor formulas meant for elephants, not tigers; donor agencies insist on “landscape units” that align with funding cycles instead of forest boundaries.

What begins as scientific cooperation turns into administrative mimicry. Local forest officers end up reporting against indicators written in New York or Geneva. The tiger, meanwhile, adapts to none of them.

This intellectual colonialism extends to technology. Satellite-based habitat assessments may suit North America, but in monsoon Asia, cloud cover renders many images useless for half the year. Yet agencies still demand them because satellites symbolise modernity. Similarly, predictive “human–wildlife conflict models” imported from Europe often ignore cultural realities of coexistence found among Indigenous and tribal communities.

When the data does not fit the spreadsheet, it is the people—not the spreadsheet—that are declared the problem. Science thus becomes a tool for disciplining local knowledge instead of learning from it.

The alternative is participatory research that begins with community observation and ends with scientific validation, not the other way around. Projects in Bhutan and parts of central India that integrate ranger diaries and herder interviews have produced more accurate early-warning systems for tiger movement than remote-sensing models costing millions. Yet such approaches attract little funding because they challenge hierarchy. True conservation science must again ask who defines “rigour” and who benefits from it.

If the measure of success cannot be translated into a local language, it probably measures the wrong thing.

Ethics drift — studying stress instead of stopping it

Science now studies tiger stress more than it reduces it. Biologists measure cortisol in scat, monitor heart rates with collars, and publish graphs describing the effects of human presence. Yet few of those graphs translate into policy change. A 2021 study in *Biological Conservation* documented multiple cases of post-collaring deaths among big cats in India and Nepal. In some, tranquilisation doses were misjudged; in others, the collar’s weight caused infections.

These incidents rarely reach the press because research institutions fear losing reputation. The animals become “sampling casualties,” footnotes in supplementary material. It is the clearest metaphor for science without soul.

Ethical drift extends to captivity research. Universities partner with zoos under the banner of conservation genetics, collecting blood or semen from animals bred only for display. The justification is that such samples might someday assist “rewilding.” In practice, they legitimise the zoo industry while diverting resources from field genomics. An EIA 2022 Telemetry Ethics Report warned that poorly supervised projects blur the line between experimentation and exploitation.

In parts of Southeast Asia, so-called rescue centres keep tigers for endless behavioural studies that have no conservation outcome. Every day spent quantifying captivity is a day not spent preventing it.

The larger question is moral: when did studying suffering become an acceptable substitute for ending it?

Conservation ethics must return to first principles—non-maleficence, transparency, and necessity. A telemetry project should proceed only if its risk to the animal is outweighed by a clear management benefit. Data that cannot save tigers has no right to endanger them.

Science should disturb policy, not wildlife.

Outro: Reclaiming duty from data

Across these eight failures runs a single thread: the abdication of responsibility. Science has become a mirror for institutions rather than a map for action. Too often it tells governments what they wish to hear and tells donors what they wish to fund. The result is a library of reports that grows as the tiger’s range shrinks.

Yet within the same system lie the tools for redemption. Open data, peer accountability, and citizen verification can reclaim truth from bureaucracy. Several initiatives hint at this future: the Global Tiger Forum’s 2023 Ranger Welfare Survey exposed how welfare gaps correlate with poaching trends; the Wildlife Institute of India’s open-access corridor database now allows civil-society monitoring of road-building; and in Nepal, community forest groups routinely audit government patrol claims through independent GPS logs.

These are not miracles—they are methods.

But technology alone cannot restore integrity; culture must change. Scientists must be rewarded for admitting error, not hiding it. Ministries must treat transparency as patriotism, not betrayal. Donors must value patience over novelty. And journals must redefine impact: a policy that saves forest is worth more than a citation that saves face. If science rediscovers humility, it can once again serve the tiger rather than measure its decline.

Ultimately, the tiger does not need more studies. It needs honesty, courage, and the kind of curiosity that acts. The forests of Asia are filled with people who already know what is happening: rangers, herders, and villagers who can read tracks better than satellite images. Science must walk beside them, not above them. The measure of knowledge is not the paper produced but the silence preserved—the unbroken call of a tiger at dusk, unheard because it is safe.

When that sound returns, data will finally have done its duty.