Introduction: Ignorence or Calculated Casualties?

Cars and train strikes kill tigers. Roads and railways cut through tiger landscapes with precision and permanence. What begins as a line on a minister’s map ends as a fracture in a living forest. Each alignment is presented as progress — faster trade, cheaper transport, national pride — yet the calculation omits the cost of silence. Asphalt and steel deliver convenience to people and extinction to everything else. For tigers, every crossing becomes a gamble against speed, weight, and indifference. And for tigers, each new road becomes an entry point for poachers.

Collisions and entry point tell only part of the story. Highways split breeding grounds, isolate gene pools, and open corridors to poachers. Trains carve through buffer zones, severing the links that keep populations alive. The infrastructure boom in tiger range countries is not accidental, as the world seems to want progress, making the construction of roads and train tracks a deliberate design shaped by profit and pressure. The budgets, nor the profits that build these lines never fund what they destroy. The ministry that counts trucks and tonnage, and even human casualties, never counts strikes on animal lives.

In India, from Kaziranga to Kanha, from Pench to Balaghat, the same pattern repeats — rails and roads running straight through the heart of tiger habitat. In Malaysia and Sumatra, it’s the same equation, written in palm oil and concrete or gravel. These strikes are not accidents of modernization. They are state decisions rendered in asphalt, proof that extinction can be planned, approved, and inaugurated — one project at a time, until no single tiger habitat is left.

The Collision Nobody Stops For

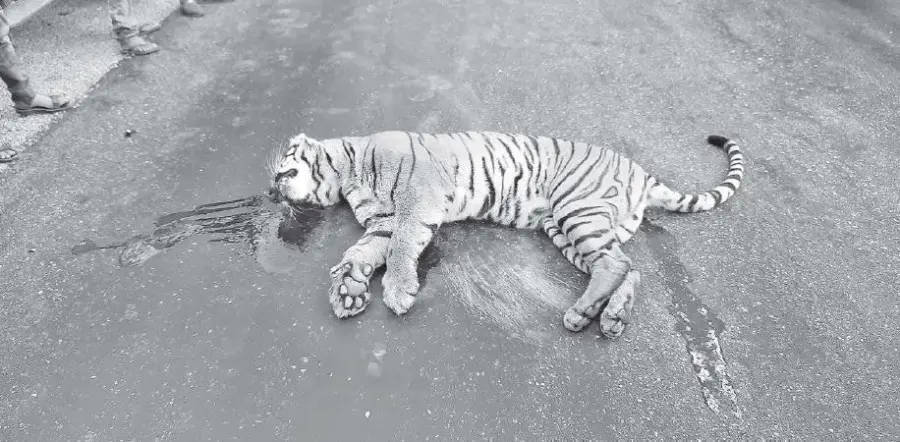

A train cuts through the dawn mist of central India. Horn low, speed high, the train crosses into a single living corridor. Minutes later a tiger lies beside the rails. It happened with Brittu, a well known male tiger who was the offspring of the famed tiger Jai. In this case a train thundered through the Sindewahi forest range in Maharashtra’s Chandrapur district. The collision on the Ballarshah–Gondia track tore through compartment 1338 and ended the life of a territorial male that had survived for over a decade in one of India’s most industrialised tiger belts.

The press note calls it an “accident,” as if steel laid through a migration path were the work of chance. There is no chance here. Every strike is the endpoint of a decision that valued freight and time and priced nature at zero.

Road and train strikes are among the most visible and yet most politically invisible causes of tiger deaths in Asia. Paperwork softens the language into phrases like “crossed at night,” “strayed from habitat,” or “unavoidable collision.” Euphemisms protect reputations, not tigers. These collisions are design outcomes, not random events. The choice to run high‑speed traffic through a corridor, to skip safe crossings, or to ignore night curfews was made long before the first paw touched ballast or asphalt.

We pretend that the tiger’s behavior is the variable. In truth, geometry, speed, and enforcement determine whether a living animal becomes a statistic. If a line on a map increases the probability of impact, that line is a design flaw. Tigers do not choose steel or asphalt; we push both through their last remaining passages and then act surprised when life tries to cross. The silence after impact is not neutrality. It is policy speaking without words.

Expanding Highways, Shrinking Forests

Infrastructure has become tiger range countries’ modern mantra. We can take each of the 10 remaining countries, as the trend is all the same. Instead of this, we have chosen to focus on India, the country that has got the most tigers to lose. Under Bharatmala, an infrastructure project within the Indian government, and allied expressway programs, thousands of kilometers of new human corridors link mines, ports, and industrial zones. On paper, these lines promise prosperity. On the ground, they slice habitats that once breathed as one. Bye bye tiger corridors.

Before a bulldozer moves, a spreadsheet moves first. Governments greenlight roads and railways when projected revenue, freight volume, and tax intake outweigh construction and maintenance costs. Because the cost of nature is not taken into account, the “cheapest” alignment is often the one that cuts through life.

Economic models reinforce that blindness. They discount long‑term ecological damage to near zero. A detour that saves a corridor decades from collapse looks “uneconomic” in the ledger. The slow fragmentation of a forest over twenty years is invisible to ministries measured by five‑year plans. By the time breeding fails and dispersal stops, the project has already celebrated ribbon‑cuttings and anniversaries. The debt is carried by those who never signed the contract: future citizens and the wildlife that cannot vote.

The same blueprint repeats across Southeast Asia. In Malaysia and Sumatra, palm‑oil supply chains need roads first, plantations second, and poachers third. Each paved kilometer becomes a new edge effect and a human footprint that widens with every season. Vietnam, China, Russia, Cambodia, Thailand: it’s all the same. Development becomes a profit instrument that treats life as collateral, deadly strikes are acceptable. The math of convenience keeps winning because it never counts the living costs. If we priced connectivity as essential infrastructure, ecological detours would be rational, not indulgent.

The Fatal Geography of Tiger Corridors

India’s tiger landscapes are a living map of broken lines. Forest patches in Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Assam, and Uttarakhand remain connected only by narrow green veins—corridors through which young tigers disperse, find mates, and maintain genetic flows. Highways like NH‑44 through Pench and rail spurs through the Kanha–Balaghat landscape have turned these lifelines into minefields. The Wildlife Institute of India (WII) has warned for years that unfenced, unmitigated rights‑of‑way behave like moving barriers that fracture populations and undermine gene exchange.

Corridor science is not abstract. Camera traps show tigers pacing at highway edges, waiting for a gap that never comes. GPS collars record detours that triple crossing time and push animals toward villages. Females abandon routes passed down for generations because the soundscape has changed. When alignments are drawn to save minutes, they can erase futures. Every bottleneck on a map represents a decision point where engineering convenience was allowed to outrank ecological survival.

The pattern repeats in Sumatra, where the Trans‑Sumatra Highway presses into peat forests that once served as safe passage. Bridges and culverts built for drainage become human entry points to make strikes possible. Poachers on motorbikes reach interiors that once took days, even weeks, to access. The geometry is intentional: each junction multiplies access, and each access point amplifies risk. We designed this geography; the tiger merely inherits it, with fewer safe choices every year.

Tiger Road Strikes — The Asphalt Deathtrap

Roads are marketed as arteries of growth. For wildlife, they are open wounds. Between 2016 and 2024, Indian field monitoring confirmed dozens of tiger road deaths, and practitioners in the landscape consistently report that the true toll is higher. Many carcasses vanish—scavenged, buried, or suppressed. Most fatalities occur on high‑speed corridors through central India where trucks run through the night and speed limits are ignored. Headlights, noise, and hard medians turn hesitation into tragedy.

In the last three years already 7 Malayan tigers have been killed by cars in Malaysia. Mind you, the number of Malayn tiger is less than 150, probably closer to 125. This means that 5% of all Malayan tigers has been killed by car strikes only.

Mitigation often fails by design. Underpasses, if available, are built for drainage, not migration. They are narrow, glare‑lit, and flood‑prone, so animals refuse to use them. Fencing stops short of funnel points and ends at gaps that become traps. Shoulders invite parking and illegal unloading. A single design error can create a mortality hotspot for a decade. When an underpass works, it is because it is high, wide, dry, vegetated, and placed where animals actually move—not where a contractor found it convenient. Permeability should be a property of the whole roadscape, not just a token culvert.

Roads do not only strike directly; they also invite killing. The same paved ribbon that carries freight also carries wire snares, steel traps, and sedatives hidden under tarps. Forest checkpoints cannot screen every vehicle. A graded spur becomes a poacher’s path, like we have seen in the case of a poached Malayan tiger, that was hidden in the trunk of a car full of poachers. In Chandrapur, Dudhwa, and Pilibhit, one new road can generate a dozen secret tracks. We call it connectivity. Tigers experience it as exposure that never sleeps.

5. Tiger Train Deaths — The Iron Corridor

Trains are unforgiving. Locomotives cannot swerve and need long distances to brake. For them it’s just impossible to strike whatever is on the tracks. From Assam’s Kaziranga–Karbi Anglong landscape to Balaghat in Madhya Pradesh, tiger carcasses by train strikes have been found beside tracks that slice through buffer zones and riverine corridors. Drivers see the flash of orange too late. Horns and floodlights rarely matter in those seconds. Signals are built to detect other trains, not life, and the operational priority is punctuality, not permeability.

Indian Railways, a website that is almost inaccessible, is the backbone of national movement in India. Its design language is capacity and speed. Wildlife mitigation is seldom a core requirement. Speed restrictions may be notified on paper for select stretches, but enforcement fades with distance from urban centers. Fencing appears in patches that do not match movement paths. Coordination between forest departments and rail divisions is episodic, often reactive after a death by a train strike. Each tiger killed by a train strike exposes cross‑ministry failure, with every department pointing elsewhere.

The cheapest line on the map becomes the most expensive line in a living landscape. Approving alignments through tiger corridors is a calculated acceptance of loss. If we already know where animals cross and when trains run, then every collision is a match between predictable movement and predictable speed. That is design, not fate. Slower night windows and detection protocols would save lives at a cost far lower than the reputational damage of preventable deaths.

The Bureaucracy of Blame

After every strike, the paperwork begins. A joint inspection is scheduled, a necropsy filed, and a letter drafted to the transport authority. Responsibility becomes a hot potato. Forest departments cite the need for curfews; rail divisions cite operational imperatives; highway concessionaires cite contractual adherence. Environmental Impact Assessments—documents meant to foresee harm—are recycled templates copied with new project names, and public consultations are treated as hurdles rather than design inputs.

This choreography protects budgets and timelines, but fail to protect ecosystems. Political cycles reward ribbon‑cuttings and completion certificates, not careful rerouting around corridors that hold the last breeding females in a landscape. Because ecological costs are externalized, agencies can claim success even as recorded tiger deaths rise. We treat each collision as an aberration; the pattern shows it is a feature. There is no accountability structure that penalizes a ministry when its alignment decision produces predictable mortality.

If the system never admits fault, learning never happens. Strike sites that should be classrooms for tigers become graveyards. The same flawed geometry is replicated in the next project because nobody pays for the damage, and therefore nobody is forced to change it. Without a rule that ties funding and promotions to measured reductions in wildlife strikes, the bureaucracy will continue to write apologies instead of redesigns, as it is ‘better to ask for forgiveness than for permission’.

Counting the Uncounted

Official statistics hide the scale of loss by car of train strikes. Carcasses are conveniently removed or are scavenged before patrols arrive. Some reports are suppressed to avoid media attention. Others are marked “unknown cause” when evidence of the strike is thin or politically inconvenient. Field staff, under‑resourced and closely monitored, learn which details to leave out. The result is a record of non-strikes that comforts policymakers and deceives the public, and a planning process that keeps repeating mistakes because it cannot see them clearly. Therefore, car and train strikes must become visible in the statistics.

Data opacity is a conservation failure. Without a transparent, nationwide database of wildlife–vehicle and wildlife–train strikes—mapped by date, GPS, time, speed, weather, and mitigation status—there is no way to prioritize fixes or evaluate whether a structure works. A camera trap that shows a tiger refusing to enter a harshly lit culvert should trigger a redesign; instead it becomes a file attachment. If the state will not count the dead by strikes properly, citizens and scientists must. Truth is the first repair, because it creates the baseline that budgets cannot ignore.

Counting also restores dignity. Every recorded death by a train or car strike is a name in the ledger of policy outcomes. When numbers are visible and maps are public, the political calculus shifts. It becomes harder to claim “minimal impact” when the dots cluster along one ministerial alignment. Visibility makes negligence expensive. That is why data are resisted. That is also why they must be demanded.

The Poacher’s Road

Every new road or siding doubles as a poacher’s corridor. Vehicles move faster than patrols and carry more than goods: wire snares coiled like cables, tranquilizers from illicit clinics, firearms disguised among tools. And it’s way easier to transport the poached animal. The same trains that kill tigers can move their bones. Trafficking follows the infrastructure we build, because infrastructure lowers the cost of crime as reliably as it lowers the cost of commerce.

In Malaysia and Sumatra, palm‑oil feeder roads become extraction corridors for timber and wildlife. In India, a highway shoulder becomes a drop‑off point for cattle that graze inside reserves. A new rail halt becomes a weekend hunting embarkation. Fire rises along new edges where people gather. None of this is surprising to anyone who works in the field. It is simply omitted from official models because acknowledging it would change the financial story that fuels approvals.

Roads and rails are dual weapons—one kills directly, the other enables killing. We cannot stop poaching with posters while paving the access routes that make it profitable. Real deterrence means closing entry points, funding night patrols matched to traffic patterns, and prosecuting the financial networks that move contraband along the same corridors used by legal cargo.

Fixing the Tracks — What Works

Mitigation is not mysterious. The tools exist.

First, alignments must avoid corridors wherever possible; the cheapest line on a map is not the cheapest once extinction risk is priced. So price wildlife.

Second, infrastructure that cannot avoid must be redesigned for permeability: properly sited underpasses or overpasses aligned with known movement paths, fencing that funnels animals toward safe zones, lighting that does not repel, and surface texture that feels natural underfoot.

Third, operations must change: night slow orders in known crossing windows, and alerts triggered by thermal or radar detection.

And harsh penalties for the ones that betray the rules. All to prevent road and train strikes.

Sensors and analytics to prevent strikes help only when they supplement good design. Thermal cameras that detect large mammals near tracks can trigger automatic horn blasts and driver alerts. Radar‑based road systems can slow traffic when movement is detected ahead. AI‑aided patrols can spot suspicious vehicle patterns near reserve boundaries. The point is not to fetishize gadgets; it is to choose what works in context and to fund it. For a deeper catalogue of effective tools and case studies, see Technology for Tigers. Technology reduces mortality, but it cannot replace political will. But it might help the politicians to recreate this system where train and car strikes kill tigers.

Structure matters too to prevent car and train strikes. Permeability is a property of the whole landscape. A brilliant underpass fails if headlights turn it into a glare tunnel. Fencing fails if it terminates at a village path. Enforcement fails if curfews exist only on paper.

Monitoring must be public, with before/after collision data and crossing‑use footage so citizens and courts can see whether structures work—and demand redesigns when they do not.

Who Pays for the Damage?

Accountability must be financial as well as moral to prevent car and train strikes. When a highway fragments a corridor, the concessionaire and the state should fund restoration as a condition of operation: reforesting margins, acquiring bottleneck parcels, maintaining crossings, and auditing results. Repair payments are not charity; they are ecological debt service, the equivalent of fixing a bridge you cracked.

We already apply “polluter pays” in water and air regulation. Apply it to infrastructure. If a mining road opens poaching frontiers, the company funds the patrols. If a highway interchange increases collision risk, the operator finances the engineering that lowers it. Toll revenues can carry a conservation surcharge audited by an independent body. When books change, behavior changes. Until then, corridors will keep bleeding for someone else’s balance sheet.

When governments and corporations refuse to listen, they must be forced to. If a single tiger were valued at US$100 million, accountability would no longer be abstract. Every collision would carry a price equal to the life it erased. In Malaysia alone, such a reckoning would cost over US$700 million in the past three years — a figure that would instantly change how infrastructure is planned, funded, and approved. Until that value is recognized in law and economics, destruction will remain cheaper than protection.

Local communities must share oversight and employment. Their vigilance is the most reliable early‑warning system a corridor can have. Funding that flows only to cement or gravel pours will not save living bridges; funding that flows to people might. When citizens are paid to measure what the state refuses to see, politics follows evidence, not only contracts.

Outro: Accountability or Extinction

India has the scale, science, and talent to lead Asia in ecological infrastructure. It needs the will to value life beyond profit, to prevent all these unnecessary car and train strikes. The tiger is not the obstacle to development; our refusal to price nature is. We designed this risk; we can design it out. Each strike is not an accident—it is a signature of neglect. Signatures can be withdrawn. Routes can be redrawn. If we fail, we will have efficient corridors and empty forests—progress measured by speed, and silence measured by the absence of roars.

A special note on accountability: when governments and corporations refuse to listen, they must be forced to. If a single tiger were valued at US $100 million, accountability would no longer be abstract. Every collision would carry a price equal to the life it erased. In Malaysia alone, such a reckoning would cost over US $700 million in the past three years — a figure that would instantly change how infrastructure is planned, funded, and approved. Until that value is recognized in law and economics, destruction will remain cheaper than protection.

Source: TIGER RANGE COUNTRIES