Electrocution

Introduction — Electrocution and Poisoning: The Silent Killers

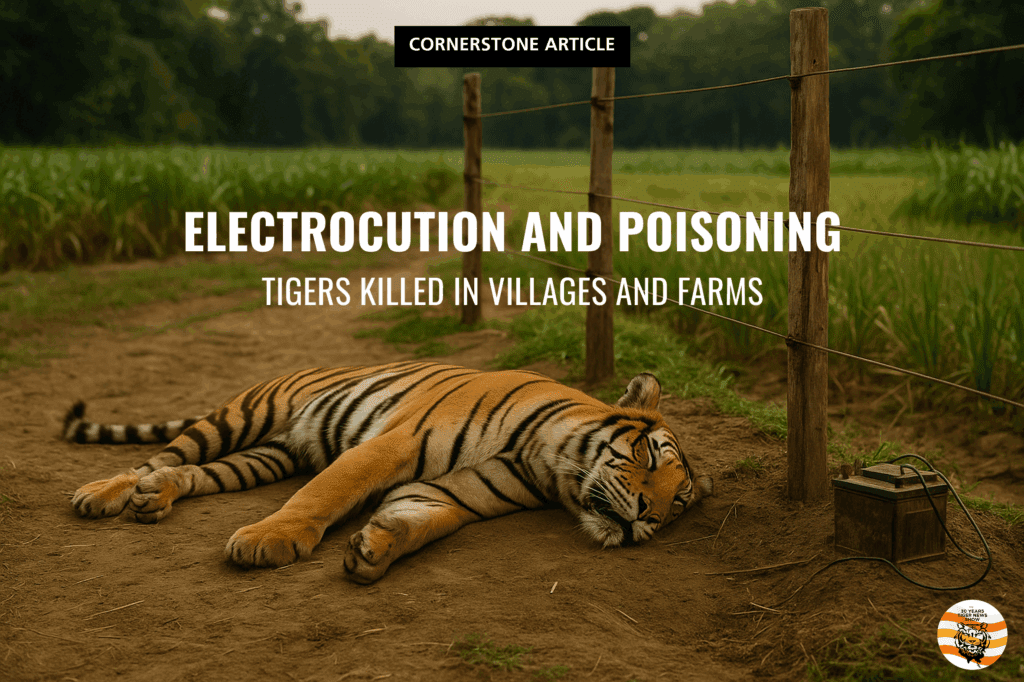

Across Asia’s tiger landscapes, Electrocution and poisoning have become a quiet machinery of extinction. No gunfire echoes, no poacher’s snare snaps — only the faint hum of power lines and the slow decay of poisoned flesh. Governments call these “accidents.” Forest departments often record them as “natural deaths.” Yet every burnt whisker and blistered paw tells a human story of negligence, greed, and evasion.

These deaths unfold in the blurred zone between village and forest, where cables from cheap transformers slice through tall grass. A tiger seeking shade brushes a live wire and collapses within seconds, smoke rising from its spine. Elsewhere, pesticide-soaked carcasses wait in the dark — a cow sacrificed to save the rest of the herd. The poison spreads beyond the tiger, killing scavengers, contaminating soil, staining rivers.

Authorities know what’s happening. They just prefer silence. Each “unverified cause” keeps statistics clean and budgets unchallenged. International partners can still cite rising tiger numbers, unaware of the quiet bodies buried under the leaves. The real story lies in those unreported fields: a crisis without bullets, conducted by the very communities entrusted with coexistence, tolerated by agencies sworn to prevent it. Behind every “accidental” death stands a system that decided long ago that some losses are acceptable — as long as the paperwork looks tidy. For a broader frame on drivers that amplify Electrocution risk, see human–tiger conflict and political failure and corruption.

How Electrocution Happens — The Methods Behind the Killings

The methods of Electrocution and poisoning are as basic as they are effective. Farmers strip live wires from overhead lines, twist them around wooden stakes, and form crude fences meant to keep wild boar or deer away from crops. The current is lethal, unregulated, and often stolen from the grid. When a tiger steps on damp soil or touches a charged wire with its muzzle, the circuit completes — death is instantaneous. At dawn, the fence disappears, rolled back into storage, and the earth is swept clean before forest officers arrive. It’s a simplified state of affairs, but nonetheless what it is — and it is Electrocution by design.

Poisoning is slower, crueler. After a tiger kills livestock, villagers inject pesticides such as carbofuran, aldicarb, or endosulfan into the carcass. The bait looks harmless; the outcome isn’t. The tiger feeds, collapses, and convulses through the night. By morning, vultures and jackals have joined the massacre, dying from the same contaminated flesh. Entire scavenger colonies vanish within weeks, yet no one investigates because the tiger, not the poison, becomes the headline. See the official Electrocution advisory and the guidelines compendium; also peer-reviewed summaries in Current Biology and Biological Conservation.

Field staff recognize the signs — singed fur, swollen tongues, the chemical odor — but their reports mostly soften the truth: “possible poisoning,” “suspected Electrocution.” The language of doubt protects everyone. No arrests, no follow-up, no headlines. And if someone asks, “it’s under investigation,” nobody asks again. Each vague file becomes a tutorial in impunity, teaching the next village how to kill efficiently, invisibly, and without consequence.

Tigers on the Edge — Electrocution Follows Encroachment

Tigers aren’t moving closer to people; people are moving closer to tigers. Forest edges have become crop lines, and protected zones now echo with the sound of grazing cattle, tractors, and chainsaws. The predator hasn’t changed its range — the human footprint has. Every new hut, every power pole, every farm encroaching into a reserve rewrites the map of fear — and raises the probability of Electrocution.

In many Indian states, herders enter protected forests daily, claiming ancestral grazing rights. Forest guards look away, often sharing the same background as those trespassing. When a tiger takes a calf, the blame shifts instantly to the animal, never to the act of illegal grazing. What follows is “protection” in the form of live wires, poisoned carcasses, or traps disguised as fences. The forest department calls these encounters “conflict.” But it’s not conflict when one side keeps losing ground — it’s colonization.

Tigers once roamed freely between reserves, guided by prey and instinct. Now they must navigate farmlands, roads, and electric grids. Every step carries risk: a voltage leak, a farmer’s rage, a policy blind spot. Governments praise their conservation achievements, but the truth is harsher — the last wild corridors are being eaten alive by cattle and politics. Electrocution is the predictable consequence of that advance. For context, see tiger corridors and tiger habitat destruction.

The Numbers Game — Electrocution Buried by Data

Official records describe most Electrocution and poisoning deaths as “unconfirmed.” It’s a bureaucratic term for avoidance — a way to close cases without investigation. The government’s tiger census highlights population increases, but those numbers exclude the ones killed quietly in fields, rivers, or ditches behind sugarcane rows. Real data lives in notebooks of field rangers and independent NGOs, not in the glossy reports presented at international summits.

Forest departments, filled with officers from farming families, often view such killings as unfortunate but understandable. Their empathy for rural communities clouds professional judgment. Few see Electrocution as a punishable crime. Many treat poison as an act of desperation, not intent. That moral gray zone is exactly where accountability dies.

In Vidarbha and the Sundarbans, documented tiger carcasses vanish before autopsies can be performed. Samples go missing. Power companies deny responsibility for live wires. Local officials file “unknown cause” reports, ensuring statistics stay politically clean. The result is systemic deceit disguised as data discipline. See reporting on Vidarbha patterns in national dailies.

Meanwhile, NGOs tracking tiger mortality estimate the real number of deaths from Electrocution and poisoning could be several times higher than official counts. But their warnings fade — drowned by government self-praise and media fatigue. Behind every chart of progress lies an uncounted body, hidden in tall grass, erased by the need to look successful. Also see political failure and corruption and political will.

Poison as Protection

When tigers die after feeding on baited carcasses, many are never counted — not because the animal wasn’t found, but because the evidence is erased in quiet, deliberate ways. Big livestock carcasses are rarely dragged away by farmers; they are too heavy. More often the carcass is left where it fell. If a tiger collapses near that meat, villagers know what follows: the body may be buried with the help of neighbours, moved at night, or simply left to decompose in dense cover. Tigers also often retreat to private, secluded spots in the forest to die alone, which further reduces the chance of detection. That instinct — to hide pain and death in brush and ravine — works, whether the animal died from natural causes or from something introduced at the carcass.

In many communities this has become a grim routine of protection. A single loss of livestock can ruin a household, so people take measures to stop a repeat. The result is a pattern: a missing or unrecognisable carcass, camera-trap gaps, local talk that never becomes a formal complaint. Forest staff see the signs — empty camera frames, quiet trails, rumours of a body moved at night — yet the official file often closes as an “unverified disappearance.” That administrative hole protects everyone: villagers avoid prosecution, departments avoid scrutiny, and ministers keep their statistics tidy.

Disappearance, concealment and communal silence are not accidental by-products; they are the social machinery that turns a death into an absence. Until investigative procedures stop treating a missing body as a reason to close a case, these deaths will continue to vanish into the landscape and into the ledger as nothing more than an item on a progress chart. As with Electrocution, the method thrives because it is quiet and convenient.

Electric Fences and the Illusion of Safety

Across tiger landscapes, thousands of illegal electric fences shimmer at dusk — thin wires stretched through farmland, often powered by stolen current. They are marketed as protection against wild boar or deer but serve another purpose: to mark and claim land that once belonged to the forest. Each fence redraws a border, one spark at a time.

Electrocution is usually filed as “accidental,” yet everyone involved knows the risk. The voltage used is far beyond deterrence. When a tiger touches the charged wire, death is instant — a flash, a spasm, a silence. Burn marks remain, familiar to every field officer. By morning, the evidence is gone: fence rolled up, poles stacked aside, the ground raked clean. The file will begin its slow bureaucratic journey under the title “unknown cause.” And that’s only one trick among many. Villagers have developed an entire catalogue of creative ways to fool the forest department — each tested, shared, perfected through years of impunity. See also official Electrocution guidance.

Inspections follow ritual form: officers arrive, take photos, and move on. Power utilities deny the stolen current; local politicians, hyenas in khadi, promise compensation for crop damage and collect easy extra votes. Forest officials step back, knowing that pushing harder risks their own position. The pattern has hardened into policy: minimal inquiry, mutual silence, and the myth that rural hardship justifies everything.

There are safer options — insulated low-voltage fencing, solar deterrents, community patrols — but they require planning and honesty. Instead, the illusion of safety endures, keeping voters calm, officials comfortable, and tigers dead: one fence, one spark, one erased report at a time. For better pathways, see technology for tigers and conservation practices.

Case Studies Across Asia

The map of Electrocution and poisoning stretches far beyond borders. The details change, the excuses don’t. In India’s Vidarbha region, homemade fences hum with stolen current every night. Officials describe these deaths as “unavoidable accidents,” though voltage readings tell another story. Farmers admit nothing, power companies claim ignorance, and forest departments file photographs instead of charges. Each carcass becomes a lesson in how to break the law and stay invisible. See coverage in Indian Express and Times of India.

In the Sundarbans, traps are disguised as crop fences, hidden between tidal dykes. Saltwater and current make a deadly mix. When a tiger dies, the community buries it fast, sometimes before officers arrive by boat. The death is recorded as “missing.” In Chitwan, Nepal, poisoned bait has become a silent tradition after livestock kills. Tigers vanish into grassland, vultures scatter, and the Department of Forests calls it coincidence. See notes via Conservation India.

Bangladesh follows the same script — Khulna villagers guarding shrimp ponds with electrified lines while officials look away. In Cambodia and Laos, the motive shifts from protection to profit: poisoned bait sold for bushmeat or medicine. Malaysia and Indonesia (Sumatra) do the same while protecting palm oil plantation margins. In Karnataka, forensic reports identified specific agrochemicals in multiple tiger deaths; see lab findings. In each case, Electrocution sits in the background as the normalized “solution” to an avoidable problem.

Each story ends the same way: with an unreported tiger, a quiet funeral, and another statistic that never enters the record. What looks like isolated tragedy is in fact coordination through silence — a regional network of neglect polished to perfection. For cross-border drivers, see palm oil and tigers and logging and tigers.

Cultural Silence and Fear

In most tiger landscapes, silence is not ignorance — it’s smart survival. Villagers know exactly what happened, who set the wire, who mixed the pesticide, who helped bury the body. But speaking out would break the unwritten contract that binds the community together: protect your own, hide the rest. Fear plays its part, but loyalty runs deeper. No one wants the attention of the forest department, the police, or the media. In remote areas, exposure means interrogation, loss of social standing, or worse — collective punishment disguised as “investigation.” This is how Electrocution becomes normal.

Forest officers rarely push too hard because they understand that silence. Many come from the same social background, tied to the same agricultural rhythms. Questioning a villager’s act of “self-defense” feels like betrayal. That empathy, misplaced yet human, feeds the pattern of avoidance. Files stay open, evidence vanishes, and everyone pretends that justice is impossible when in truth it’s merely inconvenient.

This collective quiet has become part of rural identity — a moral buffer against guilt. Elders advise youth not to speak about dead tigers; teachers repeat that wildlife deaths are fate, not crime. Even local reporters hesitate, knowing their access depends on the same officials they might expose. And so the silence grows, handed down like an heirloom. It keeps villages united, officers comfortable, and statistics clean. Beneath that quiet, the real message endures: the tiger may be sacred, but not sacred enough to risk one’s place in the village. Also see behavioral change.

Failures of Enforcement and Accountability

Every Electrocution or poisoning that escapes punishment reinforces the idea that rules are optional. Forest officers arrive late, police file “incomplete” reports, and local courts move cases so slowly that evidence rots before hearings begin. The result looks like confusion, but it is not — it’s design. A bureaucratic system built to look busy while ensuring no one pays the price.

Power theft for illegal fencing is rarely prosecuted. Linesmen from electricity boards sometimes even help restore stolen current after an Electrocution case, quietly reconnecting the same farms that caused it. Forest guards write notes instead of naming suspects because their superiors prefer reports without controversy, that’s just easier. A dead tiger becomes a paperwork exercise: forms stamped, signatures collected, tragedy converted into procedure. Everyone keeps their job, everyone keeps their silence.

Political leaders defend this paralysis under the language of compassion — claiming poor farmers cannot be punished harshly. Yet those same leaders use wildlife deaths to showcase sympathy for rural voters while blocking stricter penalties. Meanwhile, higher officials highlight “community harmony” in public statements, knowing that real accountability would expose networks of collusion reaching straight into their offices. See political will and political failure and corruption.

What Works — Real Solutions, Not PR

Real solutions exist. They just rarely come from the people in charge. After decades of failures, the first requirement is independence — investigations must no longer be led by the same forest departments that failed to prevent the crimes. Every Electrocution or poisoning should be treated as a criminal case investigated by an external wildlife crime unit or an independent task force. Only separation of power can break the circle of protection that shields offenders and officers alike.

Community engagement can work, but only when built on transparency, not theatre. In several areas, small pilot programs have reduced conflict through rapid compensation for livestock losses, community insurance funds, and shared monitoring of fences. Yet these projects survive only as long as they remain unpoliticised. Once governments move in for photo opportunities, the budgets drain away and the posters replace patrols.

Technology offers tools, not miracles. AI-based fence sensors, camera traps, and drone mapping can track both tigers and human intrusion, but data without enforcement is just surveillance. Real progress requires a triad: independent investigators, honest reporting, and punishment that actually deters. The forest department should manage forests, not hide evidence. Power utilities must audit stolen current as criminal theft, not rural poverty. Until accountability becomes a condition for funding, all “conservation” will remain a performance — polished press releases masking another tiger buried under paperwork. For solution frameworks, see technology for tigers, conservation practices, political will, palm oil and tigers, logging and tigers, and repair payments.

Conclusion — From Excuse to Justice

Across Asia’s tiger landscapes, death by Electrocution or poison has become routine enough to feel inevitable. It isn’t. Every wire, every poisoned carcass, every “unknown cause” is a choice — made by people, tolerated by officials, and protected by governments that confuse neglect with mercy. For decades, the story has been told as tragedy. But we call it policy.

Electrocution and poisoning are not crimes of desperation; they are crimes of permission. Communities act because they know the state won’t act against them. Forest officers document but don’t investigate. Politicians pose with tiger posters while funding projects that erase tiger corridors. The gap between what’s said in press releases and what happens on the ground has become the true killing field.

Justice starts with honesty — independent investigation, transparent data, and penalties that matter. A tiger’s death should trigger the same forensic urgency as a murder, because that’s what it is. Forest departments must be removed from their own oversight, and national wildlife crime bureaus must answer directly to courts, not ministries.

For every tiger found dead, there are others that simply disappear — uncounted, unburied, unremembered. Their absence defines the current era of conservation: tidy numbers, hollow pride, silent forests. The future will not be decided by compassion alone but by the courage to expose a system built on denial. Until truth itself becomes non-negotiable, every spark in a field and every poisoned carcass remains state-approved extinction. For the land-use engines behind mortality, see palm oil and tigers and tiger habitat destruction. Ending Electrocution is not a slogan; it is the baseline for any honest conservation agenda.