Turan tiger history is being pulled into today’s politics as Kazakhstan prepares to “bring back” tigers by importing Amur cats from abroad. Officials present the plan as the return of Asia’s lost king, yet the subspecies that once ruled Central Asia’s river corridors is gone and no shipment of replacement bodies can change that. What is being rebuilt is a national story, not the Turan tiger, and once again big cats are expected to absorb the risks of human decisions.

Turan Tiger Legacy And A Convenient Comeback Story

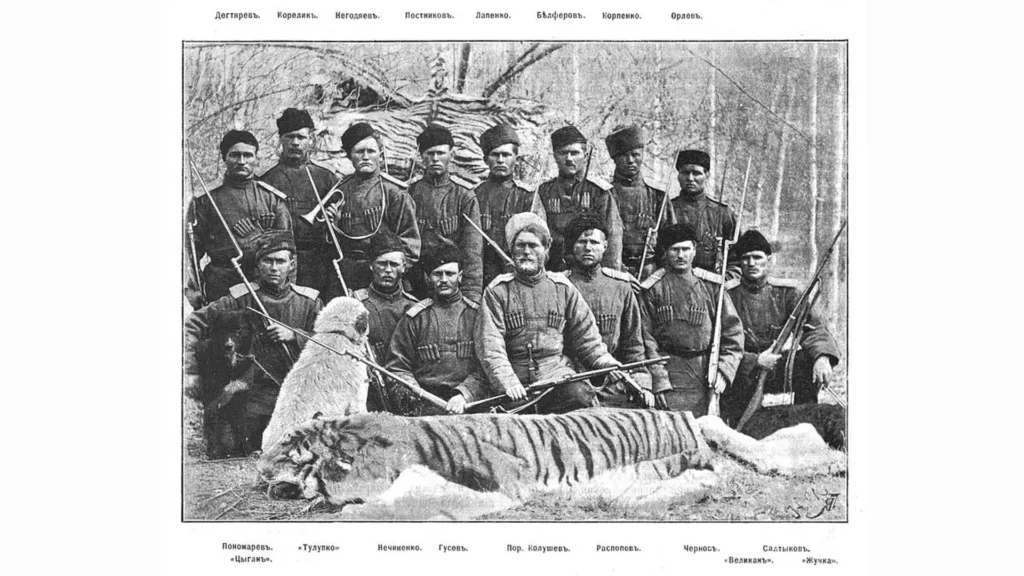

The Turan tiger, also known as the Caspian tiger, once dominated tugai forests and reedbeds from Turkey and the Caucasus through Central Asia into northern Iran and Kazakhstan. Its disappearance was no mystery of nature; it was driven by bounties, military campaigns, habitat drainage and the systematic destruction of prey herds. Today, Kazakhstan’s leadership promotes an ambitious revival narrative built around relocating Amur tigers into the Ili–Balkhash region, celebrated as Asia’s lost king returning to its range, as reported by Kursiv Media.

That framing is emotionally powerful but dangerously selective. The Turan tiger did not vanish because genes went missing; it vanished because humans dismantled its riverine habitats, drained floodplains, hunted wild boar and deer and shot surviving cats on sight. Hunting was a part of the communal behavior in Kazakhstan, like in many other countries. Unless those forces are confronted honestly, rebranding Amur tigers as stand-ins for the Turan tiger risks burying the real lessons of extinction. A project that should begin with humility instead becomes a premature celebration, with leaders claiming success long before the landscape is ready to support large predators again.

Turan Tiger Country Still Lacks The Basics For Safe Return

Respecting the Turan tiger should begin with land, water and prey, not crates and ceremonies. Feasibility studies on reintroducing tigers to Kazakhstan stress that any attempt depends on restoring wild boar and Bukhara deer, rebuilding dense floodplain forests and stabilising water regimes around Lake Balkhash and the Ili delta. Those foundations remain fragile as climate stress, upstream water extraction and development continue to squeeze the river systems that fed tugai habitats.

Releasing wide-ranging predators into a system that has not fully recovered is not a neutral experiment. When prey is scarce and cover fragmented, big cats range farther, cross roads and railways, probe livestock pastures and are punished for the stress that people created. The Turan tiger was exterminated partly because humans refused to share these floodplains; without binding legal protection, well-funded ranger forces and serious investment in coexistence backed by modern tools and corridor conservation practices, that refusal will greet any newcomers as well.

Turan Tiger Name, Amur Bodies And The Ethics Of Substitution

Project advocates argue that Amur tigers are genetically close enough to substitute for the Turan tiger, and recent studies do show a close relationship between the two populations. But wild tigers live in the present, not in diagrams. Each Amur moved into Kazakhstan, like two captive tigers from a holiday theme park in The Netherlands, will be uprooted from its home range or breeding programme and placed into a landscape that recently eradicated its cousin. If conflict erupts or funding wanes, these living tigers will be injured, removed or quietly disappear, while the Turan tiger stays a convenient brand on paper.

There is also a deeper ethical problem in using one subspecies of tiger to symbolically repair the extinction of another. Calling imported Amur cats the heirs of the Turan tiger may soothe human guilt, but it does nothing for the animals unless their new homes are genuinely secure. Real responsibility would mean protecting remaining tugai-like habitats across Central Asia, constraining destructive infrastructure, and building long-term, technology-backed patrol systems that make poaching, illegal grazing and snaring genuinely risky for offenders, not for tigers.

The Turan tiger deserves more than a marketing resurrection. Central Asia does not need a substitute king; it needs living, secure tiger populations that are never again treated as pests. If Kazakhstan truly wants tigers back, the first proof will not be the arrival of another transport crate, but a measurable shift in how land, water and power are managed. Only when those systems change can any future reintroduction honour the Turan tiger instead of repeating the choices that erased it.

Source: Kursiv.media, Kazakhstan

Photo: Abai.kz