Introduction: How Human Greed Creates Ecological Disasters

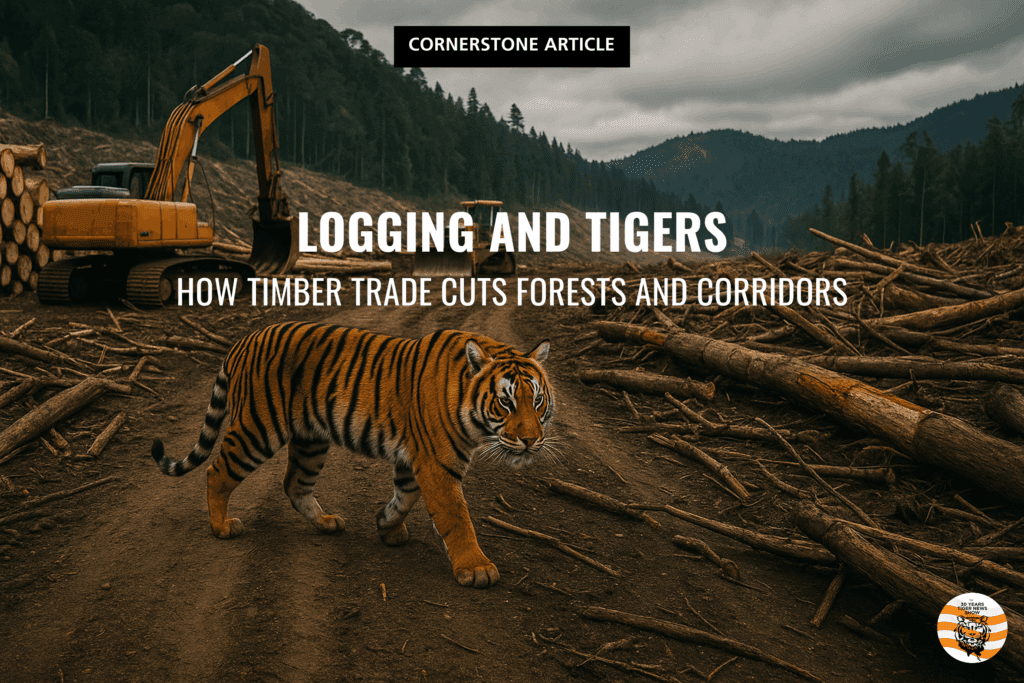

Industrial extraction did not simply happen to tiger forests. It was drawn on maps, priced in spreadsheets, and driven down newly cut roads. In Malaysia’s production forests and Sumatra’s pulp belts, the logic is consistent: convert living systems into units that can be loaded, weighed, and shipped.

The same access that moves timber also carries poachers and land speculators. Corridors that once stitched core habitats together are severed by tracks, depots, culverts, and bridges. Peatlands are drained to grow fast-rotation trees; hills are incised to keep machines moving through the wet.

The profits of logging are immediate; the ecological costs are long, cumulative, and often invisible at the time decisions are made. This article explains how the industry functions, why it persists, how large its footprint is, and what those choices mean for tigers, other wildlife, local communities, and a climate already under stress from avoidable emissions tied to timber expansion.

The Operating Machine of the Logging Industry

Across Malaysia and Sumatra, infamous because of its uncontrollable palm oil expansion, extraction follows a disciplined sequence. Concessions are drawn within production zones. Crews mark stems; bulldozers cut primary access; secondary trails branch into logging compartments. Loaders stage logs at landings; trucks or barges move them to mills or ports.

Each step is tracked by volume and time because throughput pays for salaries, fuel, and debt. Idle machines are losses, so roads stay open beyond a single harvest. With each entry, the lattice of access thickens, converting contiguous cover into a patchwork of edges.

From a ledger’s point of view, standing forest is inventory; processing adds value; exports return cash. From an ecological point of view, each kilometer of access pushes sound, light, and human presence deeper into what used to be safe interior.

Tigers do not vanish because one coupe is cut; they vanish because the web expands until movement is no longer safe. In practice, timber logistics become landscape logistics, and those logistics govern where life can still pass.

Concessions: Maps That Become Money

A concession is not just an area; it is a legal right to enter, cut, and move. That right can be insured, used as collateral, and sold as future supply to mills and exporters.

Where oversight is strong, harvest plans consider slopes, waterways, and riparian buffers. Where oversight is weak, the plan becomes a pretext. Boundaries can be “adjusted,” inventories inflated, and “degraded” labels used to justify conversion.

In both Malaysia and Sumatra, paperwork determines whether a corridor survives the next season. If a bridge location slices a riparian strip, the decision is permanent for breeding tigers that require cover along watercourses. Because timber yields are predictable and buyers are impatient, the bias is toward quicker access and more points of entry.

The damage rarely matches what the file suggests; the file counts stems, not permeability. Without public maps of concession limits, planned roads, and compliance audits, independent verification is impossible and promises mean little. And that is the opposite what we want, as the conservation value of these concessions is much bigger than expected.

Roads: The Geometry of Fragmentation

Every shipment begins with a road. Primary haul routes carry heavy rigs; secondary skid trails fan out to compartments; seasonal tracks reopen when the weather allows.

For wildlife, these lines act as both barriers and funnels. Tigers avoid high-traffic routes and shift to edges, where they risk encounters with livestock and people.

For hunters, the same lines lower the cost of setting snares and moving parts. Where road retirement is not enforced—ripping compacted surfaces, recontouring drains, and planting cover—the landscape remains permanently open, even when harvest closes on paper. A dense grid does more than fragment habitat; it also alters hydrology. Poorly designed culverts concentrate flows, scour banks, and strip roots along streams that once served as corridors. In Malaysia, road standards vary by state and by concessionaire; the result is an uneven geometry where one operator’s discipline can be undone by a neighbor’s shortcuts.

When markets reward on-time delivery of timber, the risk of overbuilding access is built into the contract.

Malaysia: Production Forests and Collapsing Connectivity

Peninsular Malaysia’s Permanent Reserved Forest is zoned by function, with large tracts legally available for selective extraction. The policy language speaks of sustained yield and regeneration, but field reality is driven by cumulative access. Spur roads slice into hills; bridges unlock crossings; and buffers are narrowed in the name of “operational efficiency.”

Even when canopy cover remains above formal thresholds, functional connectivity can fall sharply after sequential entries. Tigers that once moved between protected cores face longer, riskier crossings or none at all. Certification schemes exist and can reduce harm where applied with integrity, yet they are not substitutes for planning that caps access density and mandates retirement.

Communities are often told that roads will be closed after the last load. Without predictable enforcement, they rarely are. The result is a system that takes timber out and leaves openings behind—openings that accelerate poaching, land conversion, and fire.

Malaysia: Monitoring, Compliance, and What the Numbers Miss

Compliance is often measured in stems harvested, buffers marked, and coupes closed. It should be measured in permeability preserved. A corridor is not a checkbox; it is a measurable property of a landscape—animals still moving between cores across managed ground. Camera traps and track stations can verify that movement continues, but only if routes are planned to avoid pinch points and if access that is no longer needed is physically retired.

Where monitoring is infrequent and audits are announced, the signal is weak. Transparency is the cheapest upgrade: publish concession boundaries, approved road plans, and audit outcomes. Allow independent teams to test claims. Tie renewal to demonstrated corridor function. If timber is to be a lawful product from production forests, then the proof of lawfulness must include what remains connected, not only what was removed correctly. Otherwise the numbers look good and the landscape fails.

Sumatra: Pulp Belts and Drained Peat

Sumatra’s lowlands include some of the world’s most carbon-dense peatlands. For three decades, natural forest logging has been paired with fast-rotation plantations that feed pulp mills at industrial scale.

Peat is drained by canals to keep machinery moving and trees upright; drainage lowers water tables and oxidizes ancient carbon. During dry spells, the ground itself can burn, sending haze across provinces and countries.

For tigers, lowlands historically offered high prey density and cover. These are also the easiest places to log, drain, and plant. As corridors narrow to canal margins and roadside strips, dispersing animals face traps made from geography and access.

Plantation margins attract cattle; cattle attract hungry predators; conflict becomes a weekly word. Rewetting peat, blocking canals, and maintaining broad natural buffers along rivers reduce both emissions and risk.

Those steps must be non-negotiable where timber supply chains intersect with peat: no drainage, no permit.

Sumatra: Fire Seasons, Haze, and Global Cost

Peat fires are not lightning accidents. No, they are management outcomes. A drained block can smolder underground for weeks, hard to detect and hard to extinguish.

Smoke grounds planes, closes schools, and sends respiratory illness through cities far from the cut. Wildlife crowds into remnant fragments, pressured by hunger and heat.

The climate cost is not abstract. Emissions from burning peat dwarf the annual savings claimed by many corporate “offsets,” yet they are treated as exceptional when they are predictable consequences of drainage. In landscapes where timber moves by canal and road across drained ground, the fire risk is part of the production model.

If a concession operates on peat, hydrology must be managed for water, not speed: higher water tables, fewer ignition lines, and prioritized rewetting for degraded blocks. The cheapest timber is the most expensive to breathe.

Poachers on Timber Company Roads

The fastest way to move through a forest is to follow someone else’s investment.

Company roads meant for harvest become highways for hunting. A truck driver who sees a tiger crossing at dusk tells friends; by morning, snares appear on trails along that stretch. Wire costs little and kills efficiently. Carcasses feed the trade in parts; poison set for a pig can take down a predator. Enforcement presence is thin and predictable; vehicles avoid the same checkpoints.

Inside many remote concessions, the line between logger and poacher blurs. Drivers, machine operators, and loaders know the terrain better than any outsider — where tigers cross, where patrols rarely go, where vehicles can move unnoticed. Some moonlight as guides or informants, tipping off hunters in exchange for cash or bushmeat. Others quietly transport hides, claws, or bones out with legal timber cargo, hidden under tarps or fuel drums. The same logistics in timber that move logs to mills can move wildlife parts to traders. Corruption thrives on silence: a bribe at a checkpoint, a forged invoice, a night run without paperwork.

Real deterrence is simple to define and hard to fund: close redundant lines, gate active ones, patrol at night, and prosecute transport facilitators, not only men with snares. When the access grid is dense, the cost of hunting plummets. If timber planning treats access as permanent, the poaching problem is permanent too. If access is truly temporary, risk drops with each retired spur and revegetated landing.

Biodiversity and Water: Losses Beyond Tigers

Logging timber simplifies structure. Specialists decline when canopy continuity breaks, humidity falls, and microclimates change. Edge-adapted species increase; invasive plants exploit light along roads and landings. Seed dispersal networks falter when large frugivores retreat; regeneration skews toward hardy generalists. Hydrology takes a hit: compacted surfaces speed runoff; culverts concentrate flow; streams carry more sediment to villages downstream. Fisheries suffer; wells run muddy after storms.

None of these losses are priced into a load of timber rolling downhill. They are absorbed by communities that did not write the permits and by species that do not appear in profit-and-loss statements.

The timber fix is not mysterious: wide riparian buffers that remain uncut, conservative crossings, seasonal closures aligned with rainfall, strict off-limits zones around springs, and road retirement that is audited, not assumed.

When these basics are honored, logged mosaics for timber can still function as connective tissue.

Finance, Markets, and the End Buyer’s Leverage

Wood moves because money does. Loans, insurance, and long-term purchase contracts keep machines running. Buyers in importing countries specify dimensions and delivery dates; less often, they specify corridor outcomes. That is the missed lever.

A clause that ties payment to verified road retirement and corridor permeability changes incentives overnight. Georeferenced sourcing, independent monitoring, and public grievance logs make greenwashing costly. Insurers can price fire and legal risk higher for peat and high-conversion landscapes; lenders can require zero-drainage commitments and audited closure schedules. Public procurement can exclude timber suppliers that fail corridor tests.

None of this bans timber; it forces a choice: operate where connectivity can be maintained, or lose lucrative markets. Supply chains respond to certainty. If the rule is clear—no corridor, no contract—the line of least resistance shifts toward better behavior at scale.

Governance, Corruption, and the Rules on Paper

Paper moves bulldozers. Where concession allocation is opaque, discretion drifts toward friends and financiers. Boundaries can creep; “temporary” landings become permanent; residual stands are reclassified as degraded to clear the way for conversion.

Paper systems make laundering easy: undocumented logs can be mixed with legal stock once they cross a checkpoint with weak oversight. The antidote is boring and decisive: publish concession boundaries, approved road plans, and audit results; create independent channels for complaints; protect whistleblowers; and enforce predictable penalties for unauthorized access.

Tie renewals to demonstrated corridor function documented by external teams.

If timber is the product, transparency is the price of entry.

Without it, rules on paper serve as camouflage for outcomes that would not survive public scrutiny.

Russian Far East: A Cold-Forest Parallel

Far from the equator, the Amur tiger survives in forests of Korean pine, oak, and birch that feed deer and boar with nuts and browse. Here, too, extraction targets value: hardwoods and pines that command high prices across the border.

Roads cut on steep ground frost-heave into ruts that redirect water and erode soils. When mast trees fall, prey declines; when prey declines, tigers roam farther and risk conflict.

Collusion between traders and officials has been documented for years, with undocumented wood merging into declared flows. The lesson matches the tropics: access, impunity, and demand erode systems faster than they recover.

The fix also matches: limit new lines, retire old ones, protect mast stands, and enforce at the point of transport. The reality is that timber logic travels well; so must the rules that tame it.

Measuring Scale: What Counts as Success

Most official statistics track stems harvested, areas logged, and yields per hectare. These numbers are necessary but insufficient. The central conservation metric is permeability: are animals still moving between core habitats across managed ground after harvest?

That question is simple to state and easy to evade unless data are public. Concession maps, road density, crossing locations, and camera-trap evidence should be accessible so that claims can be tested. Remote sensing already distinguishes primary from secondary forest and plantation; pairing those layers with known corridors reveals where the risks lie.

In Sumatra’s lowlands, the map shows a tightening web; in parts of Malaysia, it shows a mosaic that can either hold together or tear depending on choices about access. Success is not fewer complaints; it is verifiable movement. If a supplier moves timber and preserves crossings, that is progress. If not, the label “sustainable” is a public relations sentence, not a biological fact.

What Must Change—Law, Transparency, Behavior

Three pillars hold up any solution.

1. Law must lock in corridor protection across production zones, not just inside parks. That includes road-density caps, mandatory retirement, and wide riparian buffers set by ecology, not convenience.

2. Transparency must make secrecy unprofitable: publish boundaries, roads, audits, and enforcement; build dashboards that show corridor status and closure progress.

3. Behavior must align with consequences: link bonuses and permits to verified outcomes; sanction operators who cut access they cannot justify; reward those who demonstrate real recovery.

Finance can do half this work by requiring zero-drainage commitments on peat and independent verification of road retirement. Importers can do the rest by refusing supply that fails corridor tests.

None of this prohibits timber; it tells the truth about where it belongs and where it does not.

Outro: Breaking the Choice That Breaks the Forest

The timber industry argues that jobs and revenue justify expansion and that modern practices make extraction safe. But the landscape keeps the score. A road that stays open is a line that cuts a corridor; a canal in peat is a fuse waiting for a dry month.

Tigers are not lost to mystery; they are lost to the steady arithmetic of access.

The fix is not revolutionary. Treat connectivity as a non-negotiable constraint. Retire what you open. Keep peat wet. Publish what you plan and what you actually do. Tie contracts to proof. If timber must move, move it from places that can bear the load without severing the threads that hold a living system together.

Malaysia and Sumatra still hold enough forest to make a different choice credible. The Russian Far East still has mast stands that can carry prey through winter.

The window is narrow, but it exists.

The only question that matters is measurable: after timber leaves, does life still pass?